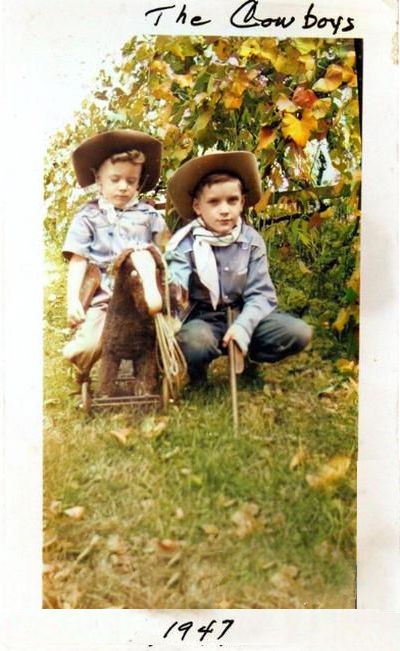

I stare at the photo. I am on a horse. From my expression I look like the horse might buck me off at any moment. I tell myself, the horse is not real. Our costumes are most likely from our aunt and uncle who live in Tombstone, Arizona. My hat is rolled funny. My kerchief is a more modest version of my older brother’s true Western scarf. His hat has that casual “I-know-what-I’m-doing buster” feel to it.

In the picture, I notice my holster is empty. With self-assuredness, my brother has casually laid his rifle between his legs. His hat is perfection. That almost-smile he has is a warning to any desperado that it would be wise not to mess with us.

We are at the concord grape arbor at our home on 5th Avenue in Kankakee, Illinois. It is late October and we are ready for any tricks – or – treats! At least my brother is. I worship him. I am two and five months and Marty will be 7 in a few days. It will be the first Halloween I vaguely remember.

We will be gone two hours but will never be further than three blocks from our home. We will return with bags loaded to the top with mostly homemade stuff. We will also be hyper and exhausted at the same time. But we are in for one final treat. My dad will tell us a very scary story, usually involving an ancient relative on my mother’s side of the family for some reason.

___________________________________

Halloween has changed dramatically since those ancient times. Churches do “trunk-or-treat”and parents buy Wal-Mart’s pre-made packaged costumes. But one tradition (my theory: the movie industry figured they could capitalize on whatever made them pee in their childhood pants): the scary story.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. To truly appreciate one of the oldest celebrations around (pre-Christmas), and know why the scary story is so important, you need a little background.

Our Celtic friends, the Druids, are said to have “invented” Halloween a few millennia ago, except it was really their version of New Year’s Eve. For them, November 1 signaled the dawning of the new year and the dark winter months that lay ahead. For the Druids, October 31 was sort of a wormhole in space where unworldly spirits could enter and get pretty nasty. To ward off these evil spirits, the Druids lit great bonfires, burnt crops and animals, and basically waited out the night, bunched up together in a corner of their little Druid hut, hoping nothing would happen, i.e., no “tricks.” To keep the kids from going out, they told them very scary stories about the goblins lurking outside.

Then the Romans came along, in about A.D. 40, and added their own touch to the Druids’Samhain with Feralia, a day they celebrated to honor the dead, and to honor Pomona, the goddess of fruit and trees. The symbol for Pomona, kind of like her trademark, was the apple, hence the very old tradition of bobbing for apples on Halloween.

About 600 hundred years later, the Catholic Church got into the act when Pope Boniface IV created All Saints’ Day on November 1 to counterbalance the pagan Samhain. Then, for good measure, about 400 years later the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day,to honor the dead. Kids dressed up as angels, saints and devils,and they had bonfires, but without the Druids’ animals. Putting all three celebrations together, they named October 31“Hallowmas.” The word “Halloween” comes from the Middle English, the “Eve of All Saints’ Day.”

The “trick or treats” business probably started about the time Christianity hit the Celts. To avoid any “tricks” from the ghosts and goblins, folks left food and other “treats” outside their doors on October 31 to pacify the scary creatures who ventured forth in the evening on All Saints’ Eve.

By the time Halloween reached America’s shores in the late 1600s, it was a time for celebrating the harvest, dressing up in costumes, and retelling stories of the dearly departed. It was more popular along the South Atlantic coast (where we live) because, as everyone knows, there are more ghosts and goblins in the South than any place else in the U.S.

Hallmark and all the costume manufacturers didn’t start seriously marketing what is now the second largest commercial holiday in the U.S. until the 1920s. Around that time, parents and kids started going door to door collecting treats. Older kids started getting serious about the tricks about the same time, including tipping over the outhouse while Uncle Henry was still in it.

Things change. With the demise of outhouses (for which Uncle Henry was greatly relieved), the most common trick was to TP(toilet paper) somebody’s front yard, usually the home of the most unpopular kid in school (who all too often became a Federal prosecutor). I remember streamers of Charmin clinging to trees, bushes, lamp posts, even over the roofs of single story houses. You couldn’t do two-story houses because (take my word for it) you could break a window in an upstairs bedroom.

But what has not changed, as I mentioned, is the telling of scary stories. I remember telling one several years ago to a bunch of kids who had gathered atthe Stoney-Baynard ruins in Sea Pines on Hilton Head Island. Candles were strategically placed in the little cubbies throughout the tabby foundation of the old plantation house, and more candles lined the pathway to the ruins. About 30 or so small children gathered to hear spooky stories. I was a last minute substitute storyteller and had to quickly come up with something scary. Since it was really last minute, I had to think of something close at hand for a prop. (Note: you always want to have at least one scary prop to tell a scary story.) As I stood at the ruins awaiting my turn, I looked up at the darkening sky and saw the story I had to tell dangling from the branches of the live oak above me: how Spanish moss got its name.

Storyteller and friend, Jimmy Littlejohn, finished up his really scary version of the Legend of the Blue Lady (a beautiful ghost, a lighthouses, and hurricanes), I pulled up the storyteller’s stool and held a flashlight up to my face. When all was quiet, I began the tale.

“This story is about the very early days of Hilton Head Island, even before it got its name. Spanish pirates used to sail these waters in search of ships to pillage and plunder. When they were thirsty they visited the island to get fresh water at the place known of as Spanish Wells.

“The most blood thirsty and evil-looking of them all was a pirate captain by the name of Gorez Goz. He was a large man — well over six feet tall, with muscles bulging from his arms that made him look like a giant. His face was deeply scarred from many battles, and his eyes were black as coal. Because he was a giant of a man, he had a giant beard—some say it grew down to his bulging belly. Like his eyes, his beard was black as coal, and that black beard, black as the blackest, starless night,was his great pride!

“One fine October evening, as Gorez Goz’s crew was carrying water from the Spanish Wells on Hilton Head Island to be taken to the pirate ship, a small group of Cusabo Indians hid behind the massive live oaks surrounding the wells. There were three of them— and old man, an old woman and a beautiful young girl. They too had come for water. They hoped the pirates would not notice their presence. The Cusabo knew the reputation of these men, knew they respected no one and put no value on the life of a Cusabo. They were all evil, but none more so than Gorez Goz.

“Just as the three Cusabo began retreating into the forest around the wells, a knife whistled by the head of the old man and sunk deeply into a tree trunk inches from the old man’s head.

“‘Hold!’ a man cried out. He sounded like thunder. The pirates stopped loading. Great blue herons flew up from their rookery nearby. Deer skittered deeply into the forest. The Cusabo trio didn’t move.

“Gorez Goz approached them. It was he who hadbellowed out the command. Even in the dimming light, the Cusabo could see the evil smile on the pirate captain’s face. He was looking at the young girl. She was fifteen and lovely. Her eyes were like large pools of the richest amber, her beautiful cheeks high, almost austere. Her long black hair sparkled in the twilight.

“The pirate captain came close to the girl, his stale breath reeking of rum and garlic.

“‘I want this one,’ he said.

“‘You cannot,’ have her the oldest man said. ‘She is my granddaughter and I am the chief.’

“‘Not for long,’ Gorez said, with a sickening smile, as he pulled out his sword, thinking he would end the old man’s life quickly.

“‘Wait!’ the young girl cried. ‘I have an offer for you.’ Giving Gorez her best smile, she continued, ‘Spare my grandfather and grandmother and I will let you chase me. If you catch me I am yours.’

“The pirate captain roared with laughter. ‘Then run my fair maiden!’ he said, laughing even louder as he watched her go her go. The rest of the pirates joined in the merriment, but when Gorez Goz turned back the grandfather and grandmother had disappeared.

“Gorez Goz cursed but took off after the girl, thinking of what fun he could have. For a big man, he could move quickly. He was sure he could catch the girl in moments. He saw her through the trees and began the chase in earnest. The light was dimming quickly, so he carried a torch with him to guide his way.

“Trailing the girl was easy: a broken twig here, a footprint in the soft forest floor there. It was as if she wanted the ugly pirate to catch her. But the chase soon took its toll on Gorez Goz. He had been at sea for weeks, and all the running started to slow him down. But just as his pace slowed, he heard the girl’s soft voice calling to him from a giant oak tree just ahead.

“‘Here, up here, you ugly oaf; climb to me,’ the girl sang.

“Gorez Goz looked up at the tree. The girl was in the high branches of a massive live oak. The pirate captain’s anger rose; he jumped to a low branch and began his climb. Higher and higher he went, and as he did, the girl climbed higher still. Gorez Goz cursed her under his breath but kept going up and up until he was almost within reach of the young girl.

“‘I have you now!’ the pirate hissed, the tree’s tiny branches at the top of the tree prickling his face.

“‘No, you ugly toad, I think the tree has you now,’ the girl laughed; and, to the amazement of Gorez Goz, she jumped from the tree. It was only then he noticed the creek below and heard the splash.

“Gorez Goz attempted to climb back down the giant oak, but the small branches held him in place. He couldn’t climb down. He decided to follow the girl into the water. It was the only way!

“But as he flung his body away from the branches they held tightly to his huge beard and would not let go—would never let go.

“The funny thing is that long after Gorez Goz died, his beard would not stop growing. It continued to spread to all the oak trees along the coast and into the forests. We now call the pirate’s beard, Spanish moss.” (Here is where I pointed the flash light up into the live oak above me and a huge mass of Spanish moss hung directly over my head. Great prop. The kids screamed.)

“And if you don’t believe me, take a piece of moss, remove the grey scales that cover it. You will see the moss itself is as black as coal!”

Copyright 2024 Saron Press Ltd.

Originally published in CH2/CB2 Magazine, 2006